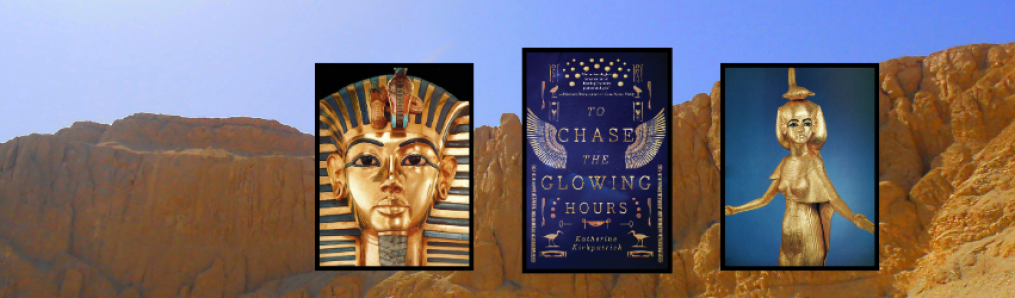

Dark blue was a favorite color in ancient Egypt. It is the color of the sky, home to the gods. Blue represents the cosmos and spirituality. It’s precious like lapis lazuli. I particularly like this color, so I am glad to see it featured on my new book cover.

Based on true-life characters and incidents, To Chase the Glowing Hours is a coming-of-age story about 21-year-old Lady Eve, who traveled in 1922 with her father, Lord Carnarvon, from her opulent home of Highclere Castle in the English countryside to the Valley of the Kings in Egypt. Her father’s hired archaeologist, Howard Carter, believed he’d found a royal tomb. A sealed doorway at the base of an underground stairway indicated that possibility. But of course, the phenomenal riches that Carter, Eve, and Carnarvon eventually uncovered would far surpass their expectations.

Gold was the color the ancients associated with royalty, divinity and immortality. King Tutankhamun’s tomb was filled with dazzling, golden objects, not least of them his solid gold sarcophagus. And since my novel To Chase the Glowing Hours (Regal House Publishing, September 2025) is about the Tutankhamun excavation, gold figures prominently on the cover. Gold also relates to the word “glowing” in the title.

I wonder what Howard Carter would have thought of my book cover. As an exacting man who prided himself on his scholarship, he would have faulted its lack of accuracy. As attractive as the hieroglyphs are, they do not spell out an actual message. They are purely decorative.

Eve, however, would have enjoyed the cover. Her emotions and her senses guided her. Beholding Tutankhamun’s treasures as they emerged from the darkness was the greatest moment of Eve’s life. It wouldn’t have taken much to remind her of that experience—the warmth of a sunny day or the scent of perfume. The Egyptian theme of my book cover would have evoked a beautiful memory.

For most people, enjoying ancient Egyptian culture is deeply connected to our senses. This is also true for me; however, reading books about Egyptian art has deepened my appreciation and understanding of it. Images that once puzzled me now resonate with clarity. Many Egyptian symbols relate to higher consciousness, immortality, eternity, and Oneness. These concepts are universal across various religions and hold personal significance for me.

The pair of bird wings on the book cover resembles wings on scarabs. The scarab symbolizes rebirth. Wings lift the soul out of a discarnate body. The newly deceased pharaoh is often portrayed as a bird with a human head, as his soul is about to take flight. Deities are also depicted with wings; like birds, the gods and goddesses travel effortlessly throughout the cosmos. According to ancient Egyptian belief, we are soul travelers as well. There is a divine part in each of us that will ultimately express itself as starlight.

I hope you enjoy the deep blue and the elegant gold designs of the book cover. I especially hope you will enjoy reading To Chase the Glowing Hours. May the novel sweep you into the sensual world of King Tutankhamun’s treasures, ancient Egypt, and the worlds beyond.