Katherine Kirkpatrick’s Interview with Kim Fairley and Silas Hibbard Ayer III

In July 1901 two New York businessmen paid the hefty sum of $500 each ($10,000 by today’s standards) to travel to a remote area of the northwest Greenland Arctic on the SS Erik. Their names were Clarence Wyckoff, 25, and Louis Bement, 35. The voyage was designed to bring supplies to explorer Robert E. Peary and to find Peary’s wife and daughter, who had departed on Peary’s ship Windward the previous summer and had not returned. When the relief party reached the Arctic, they discovered the Windward trapped in ice but the ship intact and all on board safe. Unlike Antarctic explorer Ernest Shackleton’s ill-fated vessel Endurance, Peary’s ship became ice-locked close to land. Consequently the passengers and crew easily walked back and forth on the ice to shore, where a community of Inuit helped to provide them with food and warm clothing. The Windward and the Erik sailed back together to America in August 1901.

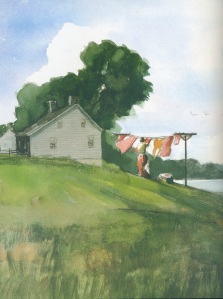

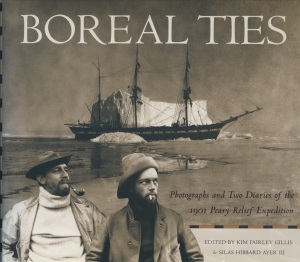

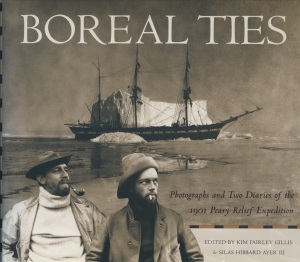

A century after Wyckoff and Bement’s voyage, their descendants Kim Fairley and Silas Hibbard Ayer III annotated their diaries and published them along with their photos in a beautiful book called Boreal Ties: Photographs and Two Diaries of the 1901 Peary Relief Expedition (2002). This invaluable reference helped me research two of my own books, The Snow Baby, nonfiction, and my new novel, Between Two Worlds.

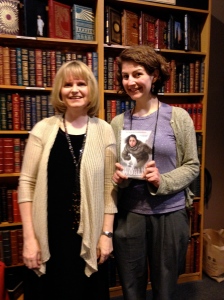

Kim Fairley is Wyckoff’s great-granddaughter. She received a Master of Fine Arts degree from the University of Michigan where she specialized in mixed media and used Wyckoff’s photographs to create large collages. She lives in Chelsea, Michigan. Silas Hibbard Ayer III, is Bement’s grandson. He lives in Ellicott City, Maryland, and is retired from his position as executive production underwriter for the Hartford Insurance Company, where he spent most of his time in Baltimore.

Cover of Boreal Ties, edited by Kim Fairley Gillis and Silas Hibbard Ayer III, published by University of New Mexico Press, 2002. Louis Bement, left, and Clarence Wyckoff, right. Copyright © Kim Fairley and Silas Hibbard Ayer III.

Katherine: Tell me about the original diaries and photographs and how they look. Where are they? How did they come into your possession? Please explain to our readers why in some cases you both own the same photographs.

Kim: Wyckoff’s photographs were given to me by his daughter, Betty Wyckoff Balderston, my great aunt, and they are still in my possession. The Wyckoff collection is in a book and is in excellent condition.

One of the things I find most interesting about the two collections is the fact that many of the images were taken seconds apart, and from slightly different angles. Since the photographs were similar but of differing quality, we were able to pick and choose the best for the book.

Silas and I have spoken about the idea of donating the collections to Cornell University, since the two men were from Ithaca and the Arctic collection of their friend Fred Church is already there.

Silas: The original diaries and photographs were handed down to me through Louis Bement’s daughter, Ariel Bement Flanagan. They were in mint condition considering they were 100 years old. The Bement pictures were numbered with an index describing the people and scenes. This index became invaluable in tracking pictures with the diary entries. The pictures were in various sizes due to the different cameras that were shared on the expedition. The pictures also were shared which explains why Kim and I own some the same photographs.

The Bement diaries were also in very good condition. The print is small and took several months to transcribe. The key to the preservation of the diary was that the entries were done in lead pencil and not ink, which has a tendency to fade and blur with age.

Katherine: When and how did the two of you meet? How did you come to publish Boreal Ties? Did working on the book enrich your lives in any way?

Kim: In writing the book I learned a great deal about my family. I feel proud of my connection to Arctic history and it felt good to be able to work on it with the descendant of one of my great grandfather’s friends. Silas and I developed a close friendship and we often talked about how Clarence and Louis would be so pleased that we had met and done something positive with their material.

Silas: Kim and I had corresponded 13 years about our Arctic collections before we met for the first time in the late nineties at the National Archives branch at College Park, Maryland. The purpose of this visit was to check out the Robert E. Peary collection to see if there were items in his collection which reflected on the 1901 Expedition and to peruse the material in our collections with the thought of donating to a museum.

At the National Archives I brought all the Bement pictures (300 plus) and diaries (2) and Kim did the same. We had over 700 pictures between us. After extensive review, I recall Kim looked at me and said, “We have enough to write a book.” Thus, Boreal Ties was born. It took a little over two years to put this together with the University of New Mexico Press.

Kim Fairley and Silas Ayer at a book signing, copyright © Kim Fairley and Silas Hibbard Ayer III.

Katherine: Tell us why the diaries and photos are of great historical value.

Kim: I discovered in running around to the various Arctic collections that our collections were unique. Most of our images had never been published, and since they were taken years before any of the explorers became bitter enemies, there was a lightness about many of the photographs. In several you see the men relaxing on deck, laughing, or conversing like tourists on vacation.

Silas: The Expedition of 1901 consisted of many who were later to become celebrated names in polar exploration, such as Dr. Frederick Cook, Commander Robert Peary, his wife Josephine and daughter Marie, and Matthew Henson, to name a few. The diaries and photos were primary source material that captured early historic moments in Arctic exploration.

Katherine: Tell us about the hardships of Wyckoff’s and Bement’s journey.

Kim: The men left in the early summer months and thought they were well stocked and prepared. What they found was that they were somewhat unprepared for the journey and at one point felt desperate when the ship was trapped in ice and forced up and onto its side. Wyckoff speaks in his diary about eating rice for a long time before he realized they had actually been eating maggots.

Katherine: Can you think of one thing about the diaries or photographs that readers would be surprised to learn?

Kim: The humanity. This is an age of great discovery and yet the subjects appear to be friends enjoying their time together. You can relate to the people. They aren’t famous explorers striking heroic poses, but down-to-earth people.

Katherine: Do you have a favorite photograph? Journal entry?

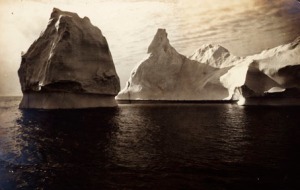

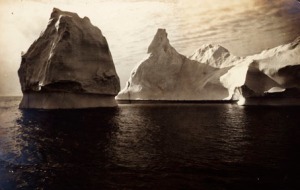

Silas: I love the photo of the iceberg in the front of the book, with the high contrast and beautiful light.

Kim: My favorites are of the Inuit, especially the expressive group photographs that show their native dress with the backdrop of the Greenland landscape.

Icebergs by Clarence Wyckoff, copyright © Kim Fairley and Silas Hibbard Ayer III.

Woman and Five Children at Upernavik by Louis Bement, copyright © Kim Fairley and Silas Hibbard Ayer III.

Katherine: How are Wyckoff’s and Bement’s photographs similar to or different from Australian photographer’s Frank Hurley’s famed 1914-1916 Antarctic photographs of Shackleton’s Endurance expedition?

Kim: Frank Hurley’s photographs are magnificent but the difference is that they seem somewhat staged and heroic in comparison to the Wyckoff-Bement photos. Wyckoff and Bement encountered indigenous people and took a large number of photographs of them. These images added a humanness that dominated the collection, unlike Hurley’s that concentrated more on the heroic nature of the expedition.

Katherine: Wyckoff and Bement, as was typical of Westerners in 1901, referred to the Inuit they met in derogatory terms as “Huskies.” Bement wrote that he “did not suppose human beings could live and stink so . . .” (p. 75) and “. . . it must be worse than a dog’s life they lead” (p. 113). But at the same time, their close-up portraits and candid photos of the Inuit hunting walrus and tanning skins appear to come from a friendly, inquiring, and respectful point of view. These photos look dignified. They contrast sharply with many explorers’ typically formal posed shots, which could almost be labeled “the powerful Western newcomer/conqueror vs. the wary natives.” Why do you think Wyckoff and Bement’s photographs are different?

Kim: The quote, while accurate, represents the racism and arrogance of the early 20th century, but from my own research, I found that these two men—Wyckoff and Bement–came to appreciate the skills and ability of the indigenous people. They embraced the native lifestyle, and applied the skills that had developed over thousands of years in a harsh environment. Their photographs bespeak warmth, camaraderie, and respect.

Katherine: I’m reading between the lines that Wyckoff and Bement weren’t just taking a “vacation” to enjoy a pleasant time. I think they journeyed to the Arctic, consciously or subconsciously, for something deeper: to learn and to grow. From what you know of Wyckoff and Bement, how did the voyage transform their lives?

Kim: The trip to the Arctic was the biggest event of Wyckoff’s life. When he returned, he started a business, married, and had children. His whole life changed. I would say that Wyckoff and Bement both went on the expedition with the idea that they might discover Peary was dead. There was rumor that he had lost his toes due to frostbite and nobody had received word from him in several months. This was in a way a secret expedition. There must have been a huge sigh of relief when they arrived and discovered that Peary was alive and well.

Katherine: Did you have an interest in the Arctic when you were growing up as a result of your great grandfather’s journey?

Kim: I didn’t know about my great grandfather until I was an adult. What I learned had a big impact on me when I did my graduate work, however.

Silas: My interest in the Arctic began when I was young and inherited a collection of letters written by Ross Marvin, Robert Peary’s personal secretary. Marvin wrote to my grandfather, Louis Bement, saying that he feared for his life but couldn’t talk to him about it. He said he would explain when he returned home. As it turned out, Marvin never made it home because he fell through the ice and drowned. Years later, a couple of Inuit converted to Christianity and one confessed to having killed Marvin. Unfortunately, the news was never made public. This polar mystery has always intrigued me.

Katherine: Tell us about your own journey(s) to the Greenland Arctic. Did you retrace your ancestor’s journey?

Kim: No, neither one of us ever made it to the Arctic region.

Katherine: Peary often gave his backers geographical names. Is there a place named after Wyckoff? Did Peary give him any carvings or other tokens of appreciation?

Kim: Wyckoff returned from the expedition with various objects that remained in the family. One was a large narwhal tusk that leaned against my great-aunt’s wall in her living room. I am not aware of any gifts to Clarence Wyckoff from Robert Peary. There was a Cape Wyckoff named after Wyckoff but I’m not sure that it was Peary who named it.

In fact, Wyckoff had a falling out with Peary when Wyckoff gave his rifle to Dr. [Thomas] Dedrick, who decided to stay in the Arctic after the 1901 expedition. Dedrick had the rifle inlaid in ivory by the Inuit as a gift to Wyckoff. When Dedrick gave the rifle to Peary to return to him, Peary donated it as his own to the American Museum in New York. Eventually Wyckoff got the rifle back, but Wyckoff was never particularly fond of Robert Peary after the 1901 expedition.

Silas: There were discussions especially with Wyckoff of assignment of names with Peary but my records do not show this was ever finalized. Peary did give Bement a full walrus head. Bement loaned his head to Cornell University with the understanding that the real ownership was to remain with me. The head was displayed in Willard Hall and disappeared in later years. I told this story to a Cornell archivist who conducted a search of the university. It was never found.

Katherine: Thank you Kim and Silas for the interview and relating so much interesting information to our readers!