INTERVIEW BY KAREN DRURY for The Historical Novel Society

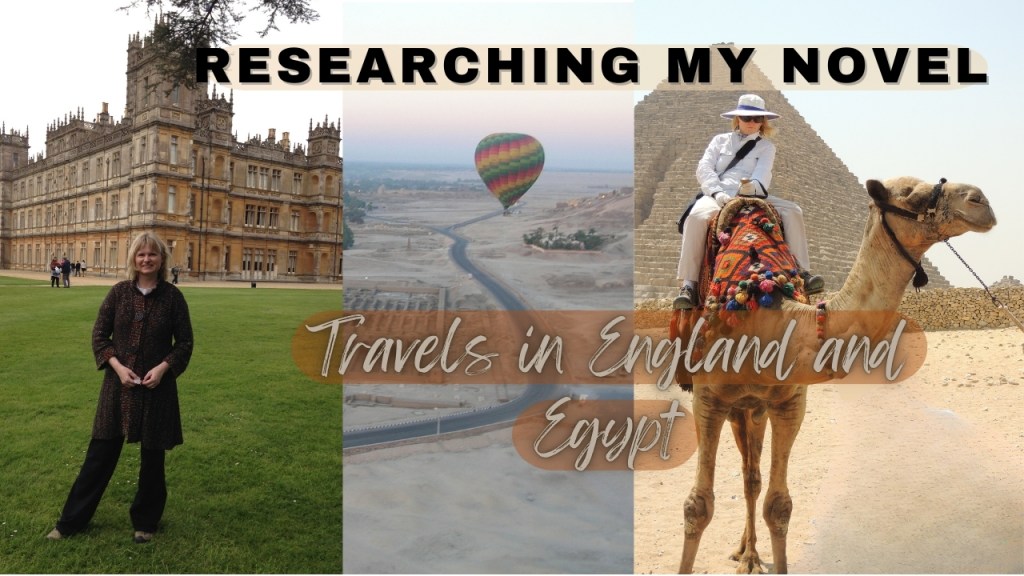

Katherine Kirkpatrick is the author of ten books, both fiction and nonfiction. When not flying over the Valley of the Kings in a hot air balloon or exploring the secret cabinets of Highclere Castle, she can be found at her computer in Seattle, Washington. Check out Katherine’s YouTube videos on the To Chase the Glowing Hours playlist.

How would you describe this book and its themes in a couple of sentences?

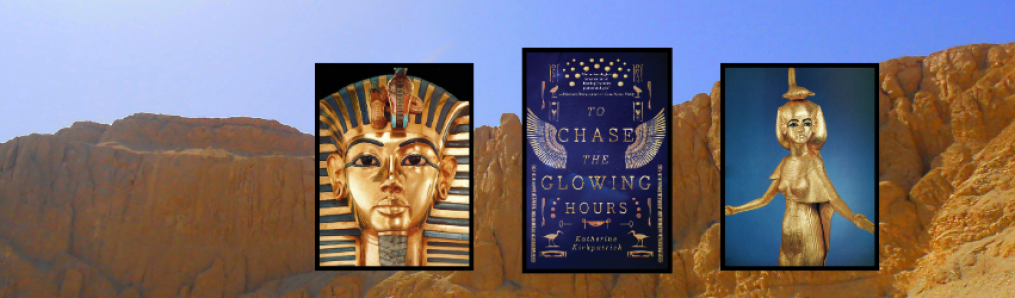

To Chase the Glowing Hours features the real-life residents of Highclere Castle, the manor made famous in the Downton Abbey television series and films. Lady Eve, the 21-year-old daughter of the Earl of Carnarvon, travels from her opulent home in the English countryside to the Valley of the Kings in Egypt. There, she hopes to realize her father’s dream of finding an intact royal tomb, that of King Tutankhamun. Amidst the excitement of her adventure, Eve finds herself drawn to the brilliant yet temperamental archaeologist Howard Carter. Set against the alluring and glamorous backdrops of Egypt and England in the 1920s, the novel explores themes of love, grief, loss, privilege, and self-discovery.

What inspired you to write this novel?

My fascination with ancient Egypt began as a young child. In 1977, my parents took my family to see the Tutankhamun exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA) in New York. I stood before Tut’s gold mask, mesmerized. Years later, as I wrote To Chase the Glowing Hours and envisioned Lady Eve entering the tomb, I tried to convey the same sense of wonder I’d felt at the Metropolitan Museum.

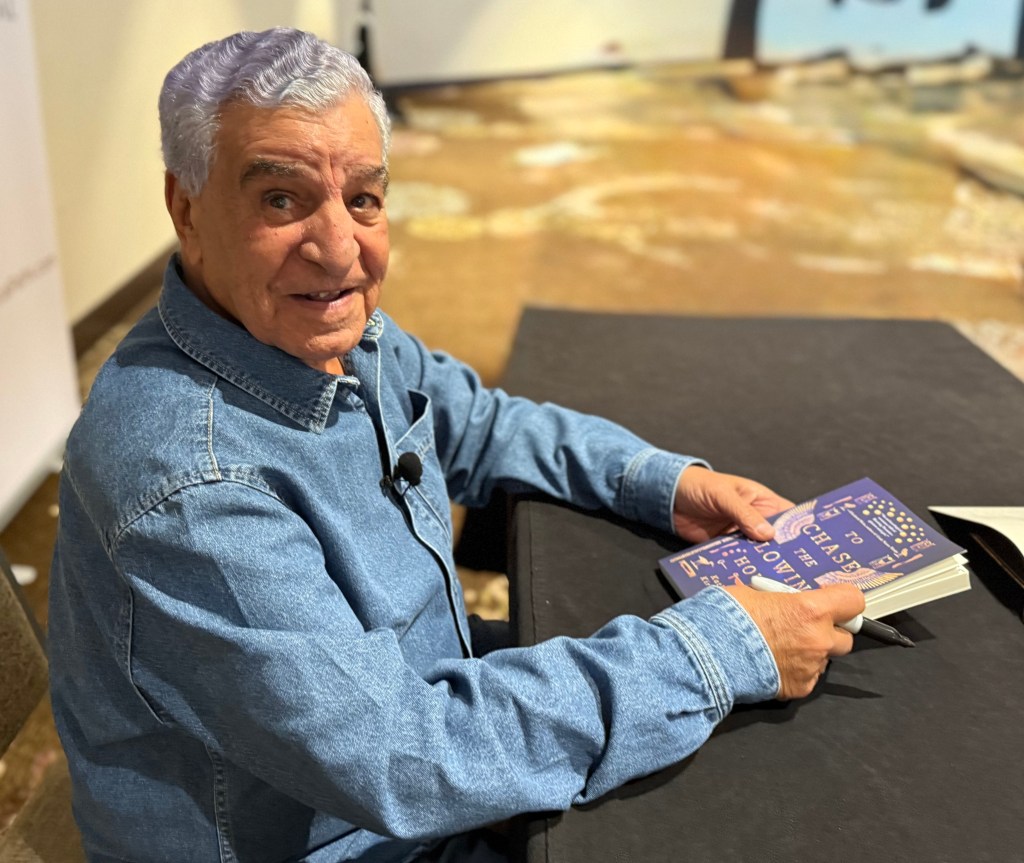

My beloved brother, the late author and filmmaker Sidney Kirkpatrick (see SidneyKirkpatrick.com), introduced me to the subject of Lady Eve and suggested I write her story. He learned of Eve when he was interviewing Thomas Hoving, a former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Hoving’s book Tutankhamun: The Untold Story contains an intriguing footnote that became the basis for my novel. Hoving found Lady Eve’s letters to Howard Carter in the Metropolitan’s archives and remarked on their gushing tone.

Would you consider writing the Egyptian side of the story?

Great idea! Someone Egyptian will have to do it. I hope archaeologist Dr. Zahi Hawass will write a novel about the excavation (he’s writing novels now, you know). Ahmed Gerigar, the chief foreman for the Tutankhamun excavation, would make a good protagonist. Gerigar was an archaeologist in his own right. He didn’t have a university degree or professional affiliation. But neither did Howard Carter (nor Lord Carnarvon, for that matter). But unlike the British men on the dig, Gerigar is never referred to as an archaeologist or Egyptologist or given much credit.

What is your research process?

I do enough book and archival research to get myself started, then continue to research while drafting. Whenever possible, I visit my book’s settings. For Glowing Hours, I toured Eve’s home, Highclere Castle, twice. That was relatively easy; my late mother-in-law was British, and I was already in a pattern of visiting England every two or three years. Journeying to Egypt was a far bolder adventure to undertake. I left my husband and two young children at home in Seattle, and joined my sister, Jennifer Kirkpatrick, my brother-in-law, Eric Zicht, and my niece, Alice, for an expedition. We stayed in the Luxor Winter Palace Hotel, Lady Eve’s hotel. We visited Howard Carter’s house. We explored Tutankhamun’s tomb, of course. We ferried down the Nile and flew over the Valley of the Kings in a hot air balloon.

What research did you leave out for this book?

Eve’s lady’s maid, Marcelle, accompanied her to Egypt on some of her trips. The Egypt scenes were better without her.

What’s hardest for you to write in fiction – real people in history, or fictional characters living in the period?

Real people. If you make up too many details, you open yourself up to criticism by readers. At the same time, if you don’t make up details, characterization falls flat. History comes to life through a character’s feelings, thoughts, and opinions.

The colonial aspects of the period might jar some readers. How do you balance the authenticity of the book and its era with modern sensibilities?

The allotment of the treasures is a crucial element of the plot. The discovery of the tomb coincided with the Egyptian nationalist movement toward total independence from Britain. Before the 1920s, foreign excavators claimed a considerable share of the findings. The Egyptian government’s insistence that the Tutankhamun artifacts remain in Egypt became the basis for a new, essential, equitable policy.

Early in the book, Eve, like her father, imagines how nice it would be to see statues from the tomb framing a great fireplace at Highclere Castle. Later in the book, she adopts a more modern point of view that the treasures ought to remain in Egypt. That change of consciousness occurs gradually over many chapters. If the character of Lady Eve had not evolved in that way, she’d come across as highly unsympathetic.

What is your occupational background, and how does that shape your writing?

For a decade after college, I worked in New York City in editorial and rights jobs at E. P. Dutton, Henry Holt, and Macmillan, and as a freelance writer and editor for educational publishers. Though I never rose high in the ranks, I learned a lot about the book business and gained contacts. I sent my first young adult novel to the Delacorte Press, to a former boss of mine; she published it, and numerous other books.

After 2000, on the West Coast, I stayed at home to care for younger and older family members. Frequent trips to libraries gave me a good excuse to see what new titles were being published. Reading lots of books aloud came with many benefits, both for my children and for me. While caretaking, I also learned to manage my time efficiently.

What’s your next project?

I’m returning to some children’s book projects for the first time in a decade.

What’s your best writing advice?

Learn about story structure before you get too deeply into a draft. Scott Driscoll, professor of fiction writing at the University of Washington’s Professional and Continuing Education department, taught me about structure. He uses Story by Robert McKee in his classes. My other advice is to make book trailers to generate excitement for your title. To see photos of the real Lady Eve, visit the “To Chase the Glowing Hours” playlist on my YouTube channel, Katherine Kirkpatrick Sketches_and_Explorations.

What is the last great historical fiction novel you read?

Horse by Geraldine Brooks. May we all aspire to writing such beautiful prose.

Thanks for the interview!

Dr. Zahi Hawass, Egyptian archaeologist.

Katherine Kirkpatrick and Dr. Zahi Hawass